Migrating Ideas and Borrowed Designs: How Cross-Border Movements of People and Ideas Shaped a Canadian Women’s Hospital (1883-1948)

By: Denisa Popa, University of Toronto

This is the second entry in a two-part series on the history of Women’s College Hospital (WCH).

Cross-border movement and its important role in shaping Canadian women’s medical history is not lost on historians (Feldberg, 2003; Warsh, 2010). Highlighting the historical impact of American influences on women’s health in Canada, this post will outline key moments in the history of Women’s College Hospital (WCH) that have shaped this institution through the movement of individuals and ideas across our southern border. This post will show how cross-border movements have shaped three key areas of WCH’s operations – education, fundraising, and clinical work.

Medical Education (1883)

Woman’s Medical College. Sketch Published in the 1892 School Calendar, Courtesy of the Miss Margaret Robins Archives of Women’s College Hospital

The history of Toronto’s Women’s College Hospital dates to 1883 with the establishment of its predecessor, the Women’s Medical College (WMC) (Kendrick and Slade, 1993). The college was founded by Dr. Emily Stowe, “the first white Canadian woman to practise medicine in Canada” (Backhouse, pg. 159, 1991). Stowe applied to the University of Toronto’s medical school but was denied admission as the university would not consider female applicants (Backhouse, 1991). Instead she went to the United States, and completed her medical degree at the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women in 1867 (Backhouse, 1991).

Dr. Emily Stowe, 1880s, Courtesy of the Miss Margaret Robins Archives of Women’s College Hospital

This experience inspired Stowe to establish a similar institution in Canada – one dedicated to training female medical doctors (Kendrick and Slade, 1993). As the organizer of the Toronto Women’s Suffrage Club in 1881, Stowe was no stranger to petitioning for women’s rights and education and “almost single-handedly lectured, campaigned and persuaded many individuals to support the establishment of the Woman’s Medical College” (Kendrick and Slade, pg. 17, 1993).

After being operational for over two decades, the medical college closed in 1906 when the University of Toronto’s medical school extended admissions to women (Shorter, 2012). The medical college’s free clinic eventually grew into the Women’s College Hospital (WCH) in 1911 (Kendrick and Slade, 1993).

Fundraising (1928)

In addition to people like Stowe, the cross-border movement of ideas also shaped WCH’s trajectory. An American marketing company, for example, was instrumental in helping raise funds during WCH’s 1928 building campaign (Telegram, 1928). Ketchum Inc (based out of New York and Pittsburgh) was contracted by the WCH building committee because the local fundraising effort was understaffed (Toronto Telegram, 1928). According to the Toronto Telegram (1928) – a committee member claimed, “[i]t would be virtually impossible to get together a local organization that could handle this matter effectively”. Thus, the American company’s marketing expertise was enthusiastically received by the committee (Toronto Telegram, 1928).

Promotional Material for the 1928 Building Campaign, Courtesy of the Miss Margaret Robins Archives of Women’s College Hospital

The goal of that campaign was to raise $750,000 (approximately $11.43 million today) in order to expand the number of hospital beds (Kendrick and Slade, 1993). The need for more beds was urgent – in 1927 over 60 per cent of patients had been turned away due to space constructions (Telegram, 1928). Canvassers mobilized throughout the city and went door-to-door to raise money. The campaign was successful and construction of the new building began in 1934 (Kendrick and Slade, 1993). The hospital was shaped, and quite literally built, as a result of cross-border support from this organization.

Clinical Work (1948)

As the hospital continued to grow, it opened a Cancer Detection Clinic in 1948 with the goal of screening healthy, asymptomatic women for the early detection of cancer (more on this clinic here) (Messner, 1992).

Cancer Detection Clinic at the Women’s College Hospital at 61 Grosvenor Street, 1950s, Courtesy of the Miss Margaret Robins Archives of Women’s College Hospital

Dr. Florence McConney – the clinic’s founder and first director – is credited for pioneering the clinic and its mission (Kendrick and Slade, 1993). Her motivation came from reading about cancer clinics that were rapidly appearing in the US in a 1947 issue of the American Women’s Medical Magazine (McConney, 1950). She travelled to Cleveland, Chicago, New York and California studying cancer clinics (McConney, 1950).

Determined to emulate these clinics in Toronto, McConney worked with Dr. Elise L’Esperance– the founder of New York Memorial Hospital’s Strang Cancer Prevention Clinic (McConney, 1950; Kendrick and Slade, 1993). In recognition, Dr. L’Esperance was invited to the opening of WCH’s Cancer Detection Clinic as an honorary guest (Cancer Detection Clinic Fonds).

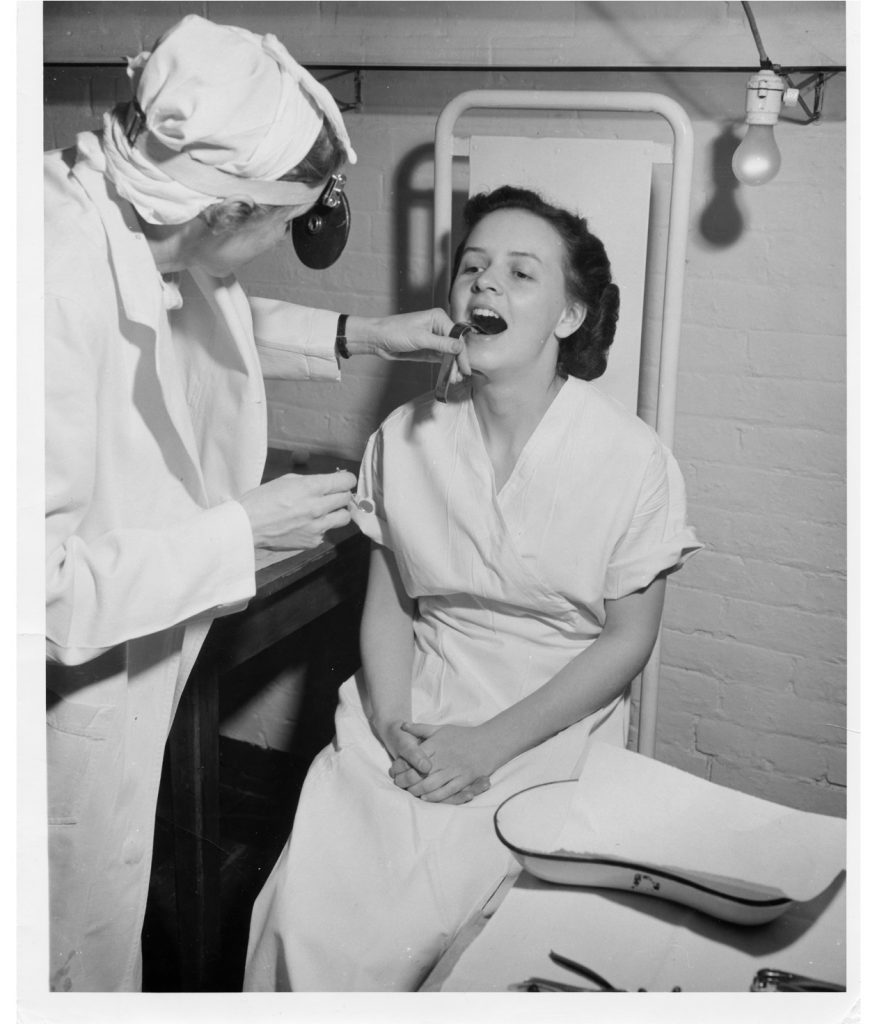

Dr. Margaret McEachern with a Student Nurse in the Cancer Detection Clinic , 1949, Courtesy of the Miss Margaret Robins Archives of Women’s College Hospital

Throughout its history WCH has been consistently shaped by American influences from multiple sources – medical training and the establishment of the WMC, marketing expertise in the building campaign and clinical work at the Cancer Detection Clinic. Interestingly, these influences seemed to originate from New York – while its proximity to Toronto almost certainly played a role, it is curious to note how frequently this particular city appears in WCH’s history. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect border closures and travel between institutions, it is worthwhile for historians to reflect on the degree of international influences in Canadian medical history.

References:

Backhouse, C. (1991) “The Celebrated Abortion Trial of Dr. Emily Stowe, Toronto, 1879” CBHM/BCHM (8), 159-187.

Feldberg, G, M. Ladd-Taylor, A. Li and K. McPherson eds. (2003). Women, Health and Nation: Canada and the United States since 1945. McGill-Queen’s University Press. (In her chapter “On the Cutting Edge: Science and Obstetrical Practice in a Women’s Hospital, 1945–1960” Georgina Feldberg continues analyzing international influences at WCH (in the field of obstetrics) from 1945-1960.)

“Campaign For Women’s College Hospital” (Toronto Telegram) April 13, 1928 in Publicity Scrap Book for The Women’s College Hospital Building Campaign (April 2, 1928 to May 21, 1928) $750, 000 Directed by Ketchum, INC. Institutional Finance Campaign Direction Park Building Pittsburgh, and 149 Broadway, New York City. Archives of Women’s College Hospital.

Kendrick, M., & Slade, K. (1993). Spirit of Life: The Story of Women’s College Hospital. Toronto: Women’s College Hospital.

McConney, Florence. Typescript: “History of The Cancer Detection Clinic Women’s College Hospital”. 1950. Folder: CDC History, Cancer Detection Clinic Fonds. Archives of Women’s College Hospital.

Messner, Sandra. Typescript: “History of The Cancer Detection Clinic”. 1992. Cancer Detection Clinic Fonds. The Miss Margaret Robins Archives of Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Shorter, E. (2013) Partnership for Excellence: Medicine at the University of Toronto and Academic Hospitals. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Typescript: “Cancer Detection Clinic”, Cancer Detection Clinic Fonds. Archives of Women’s College Hospital.

Warsh, C. (2010) Prescribed Norms: Women and Health in Canada and the United States Since 1800. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.